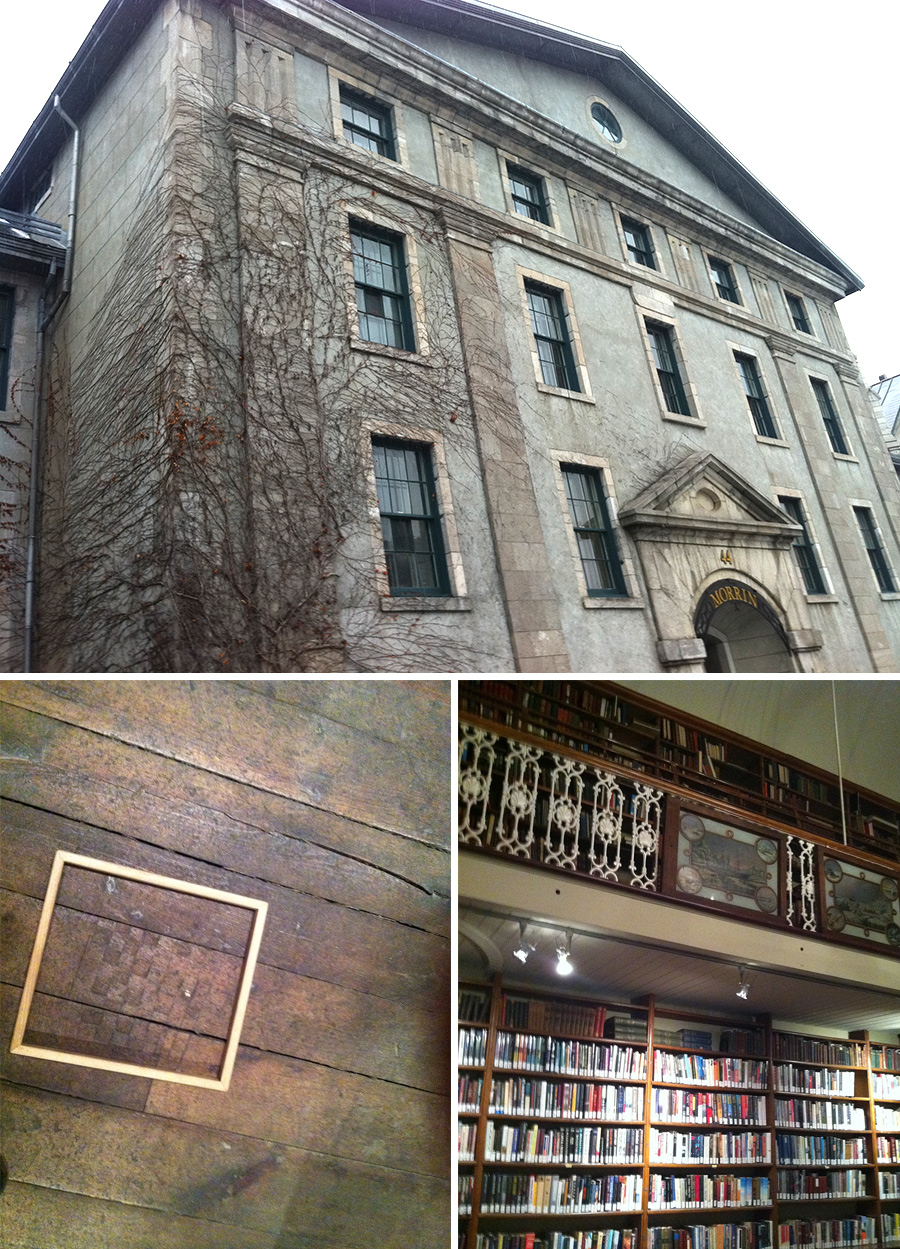

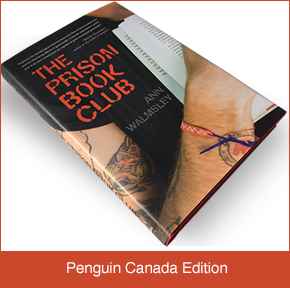

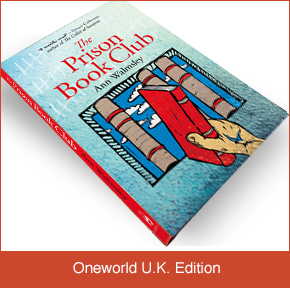

Last week Quebec’s ImagiNation Writers’ Festival graciously hosted me in perhaps the best venue yet for The Prison Book Club: Quebec’s first purpose-built common gaol and now home to a fine English-language library. A perfect pairing of a prison and books. My first glimpse of it through the snow reminded me of Toronto’s Don Jail, but older, with a severe and beautiful Palladian limestone façade . It was so tightly woven into the city’s fabric, a departing prisoner could have walked 10 paces and found himself in the close of St. Andrew’s Church. Designed by Quebec City’s leading architect of the day, François Baillairgé, and incorporating the prison reform ideas of John Howard, it operated as a gaol from 1812 to 1868 and now houses the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, which has been in existence since 1824 and has hosted such authors as Charles Dickens and Emmylene Pankhurst. After my event, I toured the building’s spectacular library and the cells, with graffiti carved into the wooden floor planks. A wood floor in a prison!